When the Susan B. Anthony dollar was issued in 1979, we thought it was the coolest thing to have a dollar coin. The problem was the size; it looked and felt like a quarter. So the first time a woman was ever put on a circulating coin in the US, the venture was kind of a dud. Until that point, I had never heard Anthony’s name. Until I was 50 YEARS OLD, I did not understand who she was, what she did, and what she sacrificed to do it.

Because of Susan B. Anthony, I can vote in an American election. Because of her, girls are empowered to act.

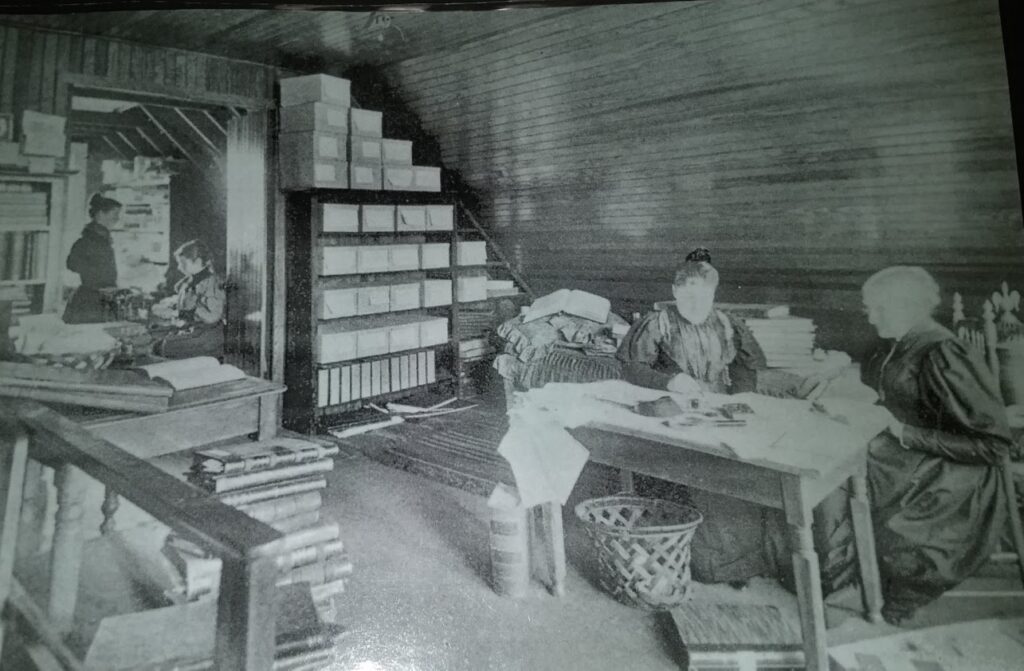

Before she worked tirelessly from her Rochester attic office, women–second-class citizens who were essentially owned by their husbands–could not cast a ballot for mayer or governor, much less president.

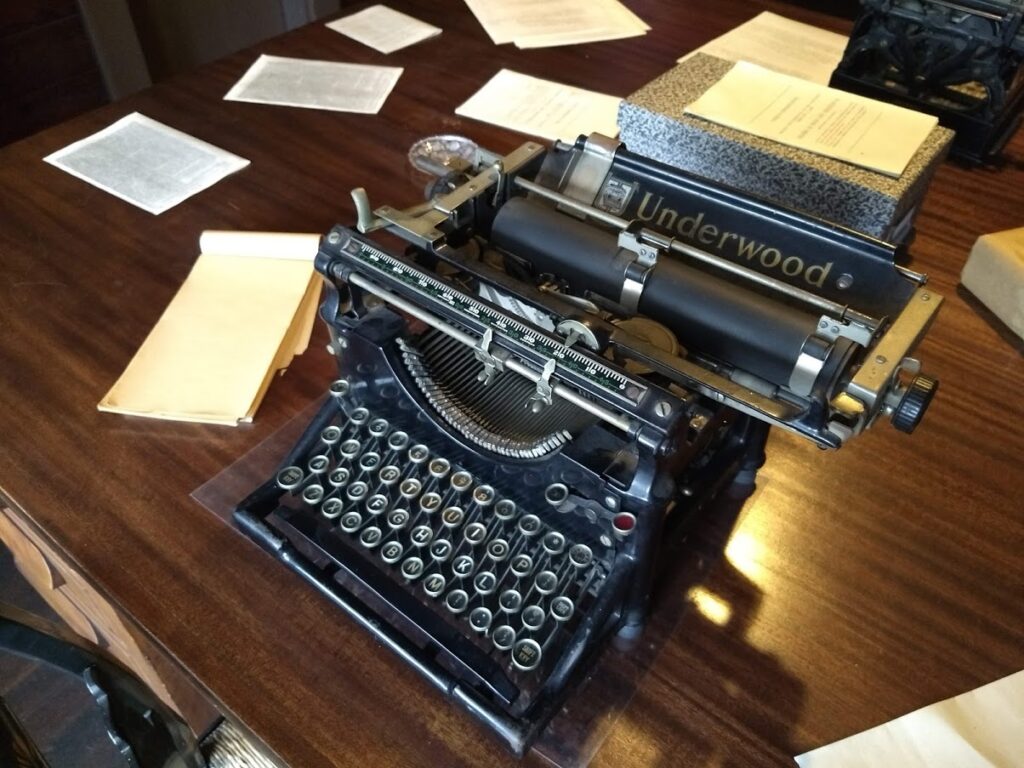

I attend a writers’ conference every spring in Rochester, New York, where Anthony’s home (and headquarters) is maintained, all the way down to her typewriter. (If you’re ever in the area, check it out.) On my last trip to western New York, some buddies and I spent an afternoon reading every word on every wall in that house, and I got an education. She was an ordinary woman who accomplished extraordinary things through grit, tenacity, and stubbornness.

Here are my top five favorite facts about Susan B. Anthony:

1. Anthony actually voted in 1872 and was arrested, tried, and convicted. It wasn’t until 1920 that the 19th Amendment passed giving women the right to vote.

2. She and Frederick Douglass were close friends, but they had a falling out over their priorities. Anthony wanted to focus on women getting the vote, and Douglass wanted to focus on Blacks getting the same. When the proposed 14th Amendment granted citizenship to Black men but left the rights of women completely out, Anthony, outraged, declared, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work for or demand the ballot for the Negro and not for the woman.” She held out hope that women would get the vote, and along came the 15th amendment, which granted voting rights . . . to Black men. Again, no women. Although supportive of Anthony’s cause, Douglass saw the fight from a different perspective.

He once said, “When women, because they are women, are hunted down through the cities of New York and New Orleans; when they are dragged from their houses and hung upon lamp-posts; when their children are torn from their arms, and their brains dashed out upon the pavement; when they are objects of insult and outrage at every turn; when they are in danger of having their homes burnt down over their heads, when their children are not allowed to enter schools; then [women] will have an urgency to obtain the ballot equal to our own.”

Anthony took the low road and even went so far as to use racist language. Douglass, on the other hand, continued to support women’s suffrage and said in an 1888 speech, “When I ran away from slavery, it was for myself; when I advocated emancipation, it was for my people, but when I stood up for the rights of women, self was out of the question, and I found a little nobility in the act.” (Teachers, if you want to take a look at a lesser-known letter Frederick Douglass wrote to Phyllis Wheatley, check out this resource.)

3. Anthony was accused of being anti-marriage because she fought for the emancipation of women. Her opponents even went after her appearance, specifically her “bloomer dress,” which scandalously did not reach the ground. She and the other suffragists who wore it called it the “freedom dress” but got so much grief for her wearing it that they decided to go back to traditional garb because the public was talking about their skirts, not their ideas.

Because she considered marriage just one more way to subjugate women, she chose to remain single.

Here’s a fascinating timeline of changes to women’s rights in the United States. It does not include voting rights. My favorite item is this gem:

A 17th-century law in Massachusetts announced that women would be subjected to the same treatment as witches if they lured men into marriage via the use of high-heeled shoes!

4. Although Anthony learned to read and write at the age of three, in her later years, she left the writing up to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, her closest ally in the women’s suffrage movement. Anthony liked both the background organizing and the public speaking, but she wasn’t the writer of the team. Stanton joked, “I fashion the thunderbolts and Susan fires them.”

Fiery doesn’t do justice to Anthony’s speeches. I especially like this 1872 excerpt and use it with my AP Lang students to help them prepare for the multiple choice section of the exam.

5. People know her best for her work as a suffragist, but in her early adulthood, she fought tirelessly for the abolition and temperance movements.

Are you a high school English teacher? Come join our community, and I’ll send you six lessons for teaching tone. While you’re waiting on that email, read this article about teaching fake news in these crazy times.