Mrs. Stewart, my high school AP Lit teacher, passed recently, and I grieved. That woman taught me formulaic writing; she reined in my verbosity (though some of you might disagree) and got me to calm down and get to the point. She did it with a formula, THE five-paragraph essay. I can clearly see myself standing beside her desk, draft in hand, asking her to translate the red scribble. I’m sure it read something like WHAT ARE YOU PROVING? We were writing literary analysis, not rhetorical analysis, but the problem was the same.

I needed a corral, and I got one in the writing formula she gave me. Because Mrs. Stewart taught me for two years in a row, she knew my writing skills. Once we got the verbosity in check, she dropped the reins and gave me some freedom. That’s how templates, graphic organizers, and formulas are supposed to work.

The brain seeks a pattern to learn.

We are WIRED to look for frames, parameters, and systems of organization. Because of that, some students need the gradual release ramp to be a really long one. What do I mean by that?

We are wired to look for frames, parameters, and systems of organization.

Formulaic Writing Instruction Versus Organic Writing Instruction

Formulaic writing is not plug and play; it’s a framework for clarity, cohesion, and organization. Typically, we think of the five-paragraph essay, a structure that ensures an introduction, body, and conclusion. Within this framework, a student must create a defensible thesis and include it early, defend it in body paragraphs, and then apply it (although that’s rarely what happens in conclusions). There’s nothing magical about five-paragraph essays; the point is intro-body-conclusion.

One of my nine-year-old’s jobs is to unload the dishwasher. I have taught him to unload the flatware tray first, then the cups, and finally the larger pots and pans on the bottom. That way, he’s not all willy nilly, randomly jumping from one section to the next and forgetting to put away the coffee mugs. That’s the formula; he is learning a pattern that keeps him from losing sight of the task, which is to unload the dishwasher completely.

Once in a while, I catch him doing something efficient, like putting away all the dishes that belong in one specific cabinet and then moving to a different area of the kitchen, unloading those dishes, and putting them away. That’s something he came up with on his own. It’s sophisticated and original.

That’s organic writing. Strong writers who have mastered the basics of constructing and defending a thesis can move on to a less formulaic approach. They might not have a tidy little thesis statement in the introduction; that thesis may develop over the course of the essay and blossom in the conclusion.

In AP English, we want our students to demonstrate an ability to write on the college level, and that skill set includes an open, debatable thesis, a flowing line of reasoning that moves from one paragraph to the next, and a conclusion that actually says something.

I think we can teach our budding writers to do that with formulaic writing instruction. The five-paragraph essay (or four- or six-) has a bad rap; it actually teaches students how to put their pants before we teach them about the haute cuture fashion industry.

Our students need to be able to put their pants on.

This Lumen Learning article breaks down the different between formulaic and organic writing (academic writing), but I think the author of this site fails to see that we can teach sophistication and structure at the same time. This explanation differentiates between a formulaic thesis statement and an organic one in that the formulaic thesis includes a blueprint while the organic thesis is open. I teach students to write an open thesis within a formulaic essay, so there can be a marriage between the two.

Gradual Release in Rhetorical Analysis

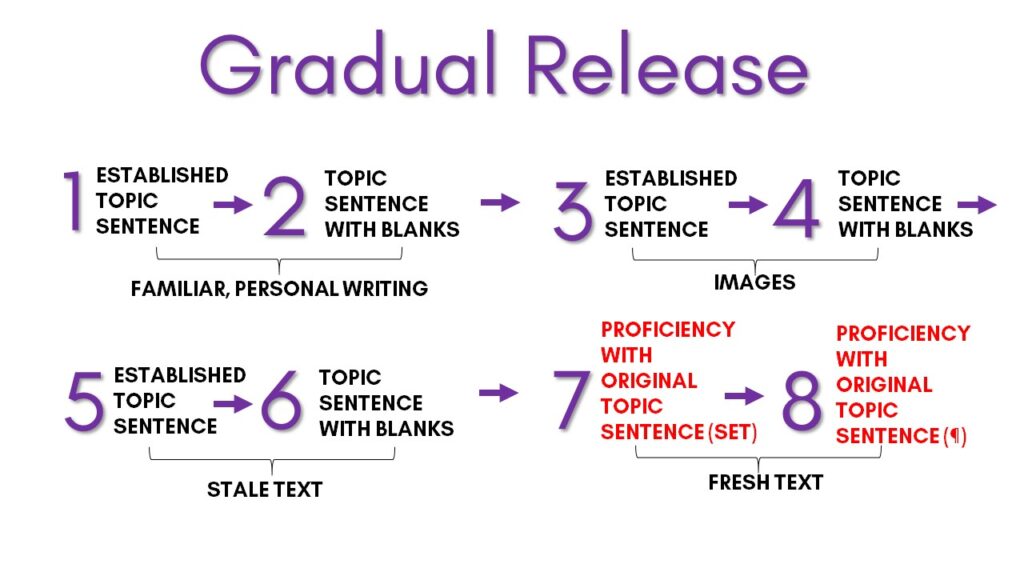

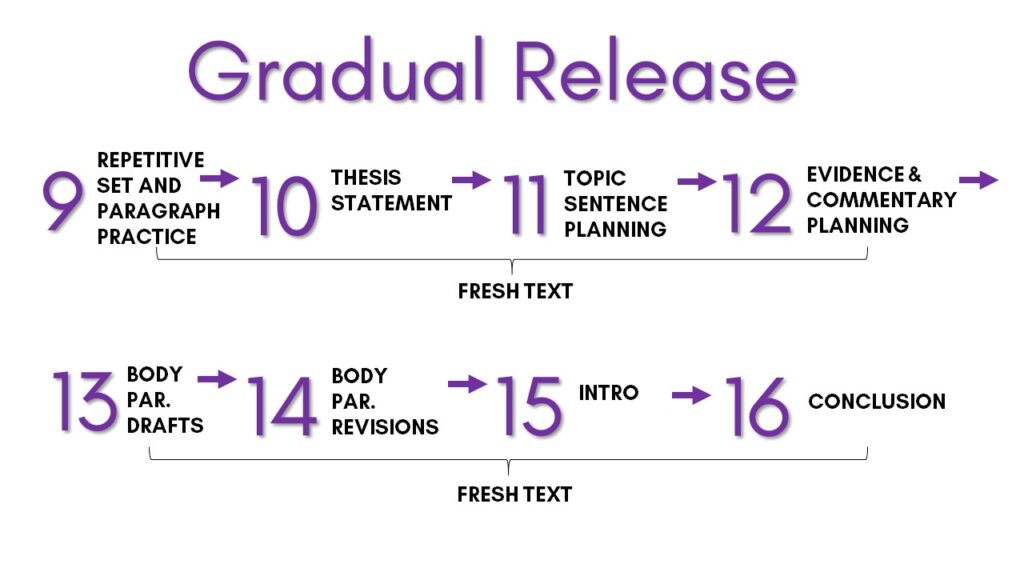

Gradual release (or scaffolding) is simply the process of giving students a LOT of support when introducing a skill or process and then removing the supports a bit at a time until the student can perform the skill or process alone without help. For example, when I’m teaching rhetorical analysis, I know that what’s coming is a student staring blankly at that commentary brick wall, waiting for the idea fairy to come land on his head. I like to get a jump on that blank stare and start early in the process to teach what commentary is at a rudimentary level. When we get to the rigorous stuff, they are ready. We use a sixteen-step process to get them just to a full body paragraph. I know, I know. Over the top. Guess what, though? My students don’t get stuck on commentary like they used to.

Here’s where templates come in:

Kahn’s _____________ tone is illustrated by her use of ________________.

We start at the topic sentence level and work on tone, tone, and more tone. Tone is meaning, and if a student misinterprets how an author feels about her subject, it’s over. I teach a very basic topic sentence with one tone and one device. It’s basic, elementary, simple, and CRUCIAL for students’ understanding of author’s purpose. But Angie, you say, you’re going to build bad habits because students are going to get stuck in talking about isolated devices and never connect to the author’s purpose. Patience, grasshopper. This is the Kindergarten template.

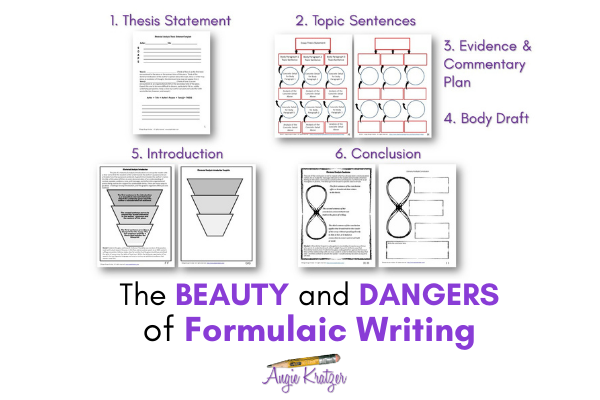

We move from sentence templates to evidence/commentary color coding to body paragraph graphic organizers to intro organizers to conclusion organizers. This is what the whole process looks like.

How Formulaic Writing Can Support Student Learning Through Differentiation

The beauty of formulaic writing is that it gives weak writers a framework, something to hold on to, a place to start to building. I can’t steer a ship that’s not moving, right? I know–enough with the metaphors already. A writing formula gets the ship moving so that I can steer it. If a student comes to me during in-class conferencing with a topic sentence and some evidence but no commentary, we go back to the frames I gave the student. We’re not pulling commentary out of a hat; we’re using it to tie the evidence to the debatable idea in the topic sentence. I can confer in a particular way with this student because of the templates and graphic organizers I require when I am training students to analyze rhetoric. I can ask these questions of a weaker writer:

Is your topic sentence debatable?

Is your evidence specific?

Does your evidence defend the topic sentence?

Real talk here for a sec: Some students will always rely on a formula, and that’s ok. I’m a terrible bowler; I don’t practice, my form stinks, and I’m not very strong. Fortunately for me, I have an eight-year-old son, and he bowls with the kid gutter guards. I feel like a pro when I bowl with him! We have a good time, and I go home feeling not-so-loser-ish when I get to bowl with his kid rails.

The Danger of Formulaic Writing

The danger of the five-paragraph “theme” is that we can lock students in to that framework and never try to move them out of it. A student moves from one teacher to the next and just gets better at the formula. That’s ok for some students, but there are many who need to break out completely. There are exceptions, but students who live in the formula don’t generally make 4s and 5s on the AP Lang exam. Those are the writers who might come to you needing to be reined in a bit but who do not need to be trapped in a formula.

For some students, the patterns may stifle them and keep them from getting the sophistication point.

By the time students get to AP Lang, formulaic writing is going to serve best the students who need to move from a 2 to a 3. Those students would benefit from my unit Rhetorical Analysis for Every Student. If you’re trying to get this work done with AP Lit students or pre-ap students, try Literary Analysis for Every Student.

Two Kinds of Student Writers

I have mainly taught two kinds of writers in my 30 years in education: those that need the confidence to take risks and those that need their confidence to match what is actually happening on paper. The first group needs the framework to build their confidence through skills. These students will use templates and graphic organizers longer than the second group. That second crew needs to trim the fat, get to the point, mow down the flowers, and get control. That group will use the templates and graphic organizers once or twice just to see where I want them to go. I keep them contained for a while and then let them out earlier than I do the first group.

On a practical level, two months into a semester, differentiation might look like this: All students have demonstrated proficiency with topic sentences and evidence, and half the class is rocking commentary. The half that has a solid grip on topic sentence, evidence, and commentary has more choices in planning than the other half does. I might have two or three graphic organizers copied and stacked on a table, and they can use them if they need to use them. Some students will, and some won’t. Some of the proficient students will plan some paragraphs without a graphic organizer and some with a graphic organizer.

Just like I tell students that they aren’t allowed to use fragments rhetorically until they can control their own sentence structure, the same rule applies here: You can break the rules once you show me that you can follow them.

The other half of the class is locked in to the formulas until they are proficient, particularly at commentary. A student cannot grasp commentary until he or she is good at crafting a debatable topic sentence and specific concrete details that contain evidence defending that argument. Those folks are hanging out in the corral for a while.

Do your students get STUCK on commentary? Do you look up from your desk and see that blank-I’m-waiting-for-the-idea-fairy-to-come-land-on-my-head look? If so, get this freebie, 6 Questions to Beat Rhetorical Analysis Paralysis, a commentary anchor chart to help your students get unstuck.