Let’s not complicate things. Line of reasoning standards in most curricula ask students to do two things:

- Make sure that everything—and I mean everything—in a piece of writing defends one central controlling idea (i.e., claim or thesis).

- Trace an author’s/speaker’s progression of thought in defending one central controlling idea.

The Concept Isn’t New

Because the AP Language rubric now includes this wording, we’re paying more attention to it, but we’ve always required students to defend one idea. What we haven’t always done is ask them to trace that defense in someone else’s writing.

Most curricula now use the language “line of reasoning” as evidenced by the following:

AP Language:

REO 5.A Describe the line of reasoning and explain whether it supports an argument’s overarching thesis.

REO 5.B Explain how the organization of a text creates unity and coherence and reflects a line of reasoning.

REO 6.A Develop a line of reasoning and commentary that explains it throughout an argument.

REO 6. B Use transitional elements to guide the reader through the line of reasoning of an argument.

Common Core State Standards:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.4 – Present information, findings, and supporting evidence clearly, concisely, and logically such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to purpose, audience, and task.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.11-12.3 – Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric, assessing the stance, …

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.11-12.4 – Present information, findings, and supporting evidence, conveying a clear and distinct perspective, such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning . . .

SL.CCR.4 – Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning . . .

TEKS even uses this language in a new course, Introduction to Engineering Design. Students are asked to “present information, findings, and supporting evidence clearly, concisely, and logically in oral presentations such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development, substance, and style are appropriate to purpose, audience, and task.”

Line of Reasoning is Everywhere

This is the definition in a nutshell: A writer has one central argument to make to the reader or listener. Every topic sentence, piece of evidence, and line of commentary makes that argument.

We’ll hit three ways to teach the concept.

Strategy #1: Illustrate with Animation.

I created a video for you with some simple moving graphics to help students understands how the connections happen. The video stresses commentary as a connector.

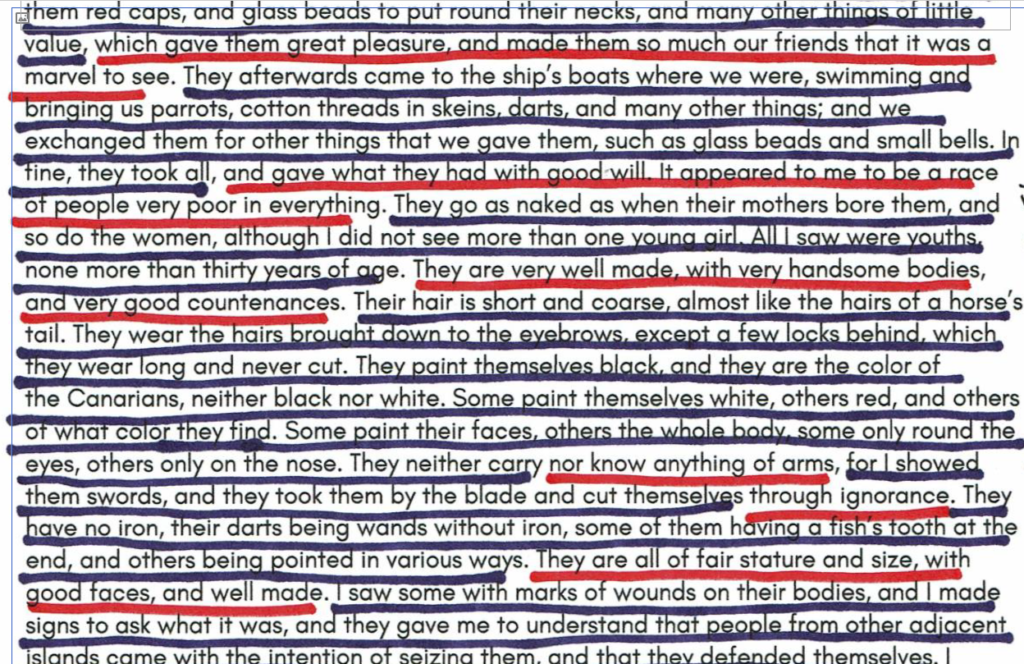

Strategy #2: Use Color Coding to Track.

Teach students that all opinion/commentary is red. Fact/evidence is blue. When defending a thesis, students write with colored pens or pencils or write within color-coded graphic organizers. While tracking LOR, students underline with red and blue writing instruments. You can read more about color coding here.

Tip: When showing students what LOR looks like, use a text that does a really good job with that thesis-centric flow. Start the analysis with SOAPS (subject-occasion-audience-speaker-purpose) and focus on author’s purpose. Students then color code the text, focusing on blue for fact and red for opinion. A strong LOR will have nothing BUT blue and red. Anything else is fat to be cut.

In my own unit, I use a translated excerpt from Christopher Columbus’s 1492 journal (what a revealing look at his perspective on indigenous people, by the way) and the transcript of an interview with Harriet Tubman.

Strategy #3: Have Students Create Analogies.

As reinforcement after the concept, have students develop analogies to solidify the content. In Robert Marzono’s Classroom Instruction that Works, he reveals that analogies are some of the most powerful ways to help students make connections between what they already know and what they are learning.

As always, model first. Create an analogy that illustrates the concept. (I’m using the modeled-shared-guided-independent framework here, also known as me-we-few-you. Once you get to the independent part, differentiate by giving students a starting point, like a list of concepts that lend themselves to this comparison.)

You might try

A car (The engine is the thesis. Evidence is the pistons, carburetor, and spark plugs. What flows through that whole system making it work as a whole is fuel. Fuel is the line of reasoning.)

The human body (This one could go in 80 different directions, but students might use something with the cardiovascular system. For example, oxygen is the thesis. Arteries carry that oxygen to get it to parts of the body that need it.)

A garment (Thread holds the pieces of the garment together. Line of reasoning is the thread.)

A box put together with dovetails and glue (LOR is the glue.)

An alternative, albeit a tiny bit lower on the rigor scale, is to give student analogies that DON’T work and have them break down where the analogy breaks down.

The only trick is to make LOR more clear than complicated.

Go in depth with line of reasoning with these five detailed lesson plans.

Contents:

◈Lesson 1: Analyzing Line of Reasoning

◈Lesson 2: Organization in Line of Reasoning

◈Lesson 3: Creating a Line of Reasoning in an Argument

◈Lesson 4: Creating a Line of Reasoning in Analytical Writing

◈Lesson 5: Transitions and Flow of Thought

◈11 Handouts and Graphic Organizers

◈Print and Digital Versions