What is spiraling?

The concept of spiraling clicked for me when I was a curriculum specialist. (For three years, I came off the front lines and served as Secondary Writing Curriculum Specialist for a large district in North Carolina. I served the ELA teachers at 47 middle and high schools by coaching, facilitating professional development, creating pacing guides and curriculum maps, and designing a writing benchmark system.)

Simply, the idea of spiraling is that a teacher introduces a skill, helps students get to proficiency, and then leaves the skill for a time. The teacher then comes back to the skill, drops in to work on it again, and then leaves to teach something else. The teacher continues to drop back in to the skill. The ideal is that we get students beyond proficiency to mastery, but the realistic goal is that we just keep students at proficiency and prevent a slide backwards.

I think of it like spinning plates. In the illustration below, the performer would start spinning the purple plate on the left. Once that one is going strong, he moves on to the aqua plate next to it. Once that one is going, he gives that first purple plate another spin to keep it going. If he doesn’t, that plate will stop and fall off the pole. So now, the purple plate and the aqua plate are going strong. He gives that aqua plate another spin and starts the orange plate and so on. In an English classroom, we complete this process constantly.

How English Teachers Spin Plates

We’ll use a punctuation issue as a clear-cut example and then move on to the fuzzy stuff. The purple plate is comma rules. I teach 20 rules, so of course I expect students to remember them all the first time I teach them, right? Right. I move on to my aqua plate–let’s say that’s an introduction to argumentation–but I forget all about comma rules. Months later, by the time we’re over at that yellow plate, my students are like, Comma rules? What comma rules? What are these of which you speak? I needed to keep dropping back in to comma rules during revision activities, bell ringers, etc. That’s how spiraling works.

An Application to Rhetorical Analysis in AP Lang

I begin the year with rhetorical analysis. I’m an oddly linear thinker (especially for an English teacher), so I teach RA then argumentation and then synthesis. (If you’d like my pacing guide, it’s all yours. You can grab my 180-day guide here and my 90-day guide here.) Because my students are dealing with rhetorical analysis in August, September, and October, I have to deal with it again before the May AP Lang exam. There are several ways to do that.

5 Ways to Spiral

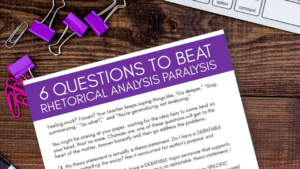

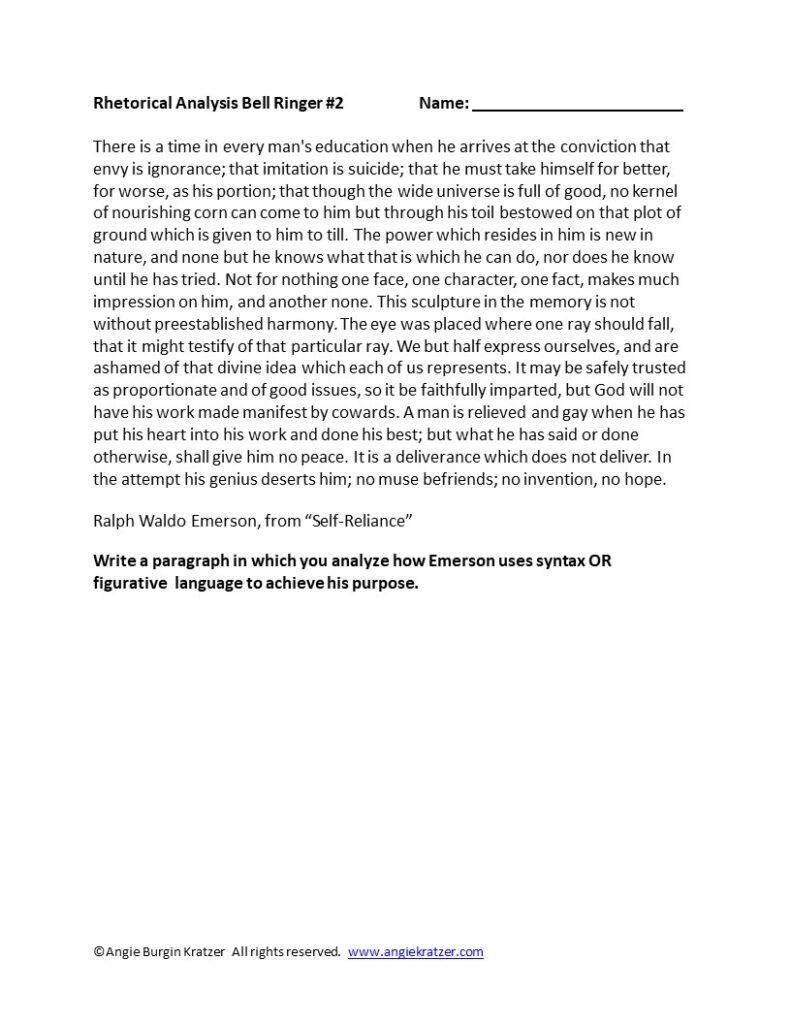

- Use writing bell ringers. Even though the focus of a lesson may be on constructing an argument, the teacher can still spiral rhetorical analysis. Use a short excerpt of a non-fiction passage and give students a one-sentence task. For example, a student might be asked to discuss how Emerson uses figurative language to achieve his purpose in a one-paragraph excerpt. The preview for this resource is a freebie. Test drive the exercise to see how it works for your students.

- Use RA multiple choice bell ringers. Multiple choice practice doesn’t have to be a full-blown 45-question event. We can give students one, two, or three questions about one passage just to keep rhetorical analysis skills fresh. Each of my published multiple choice practice sets has a preview you can download and use with your students.

- Back up and start gradual release again. Gradual release is the modeled-shared-guided-independent system of removing the supports students use as they are becoming proficient at a skill or process. If you use this model with rhetorical analysis and it has been a while since students wrote a timed essay, spiral by going back to modeling or sharing. If you would like to learn a bit more about gradual release, join me for my January webinars. I’ll announce the dates in my Facebook group.

- Organize a gallery walk. Post several released AP Lang exam released Question 2 prompts around your classroom. Students rotate through the prompts, read them, and choose one of three organizers for each one. Students have to sketch out the rhetorical triangle, SOAPS, or SPACECAT for each prompt. (A cheat sheet would be helpful.) Then put students in small groups, assign each group a prompt, and have each compare notes and write a thesis statement.

- Segment timed practice. As students work up to spending 40 minutes(ish) on one timed essay, consider breaking up that time within a class period.

- Distribute a prompt and give students ten minutes to read, sketch out SOAPS (or SPACECAT or the rhetorical triangle), and write a thesis. Stop and debrief. Did you have any trouble identifying tone? Let’s hear some of the thesis statements.

- Give students five minutes to sketch out a rough plan. This might look like a web, outline, or tree diagram. It could be just topic sentences. Stop and debrief. Where did they focus?

- Give students 20 minutes to write a draft. Stop and debrief. Was it hard to balance evidence and commentary? Did they bite off more than they could chew?

- Give students five minutes to proofread. Stop and debrief. Where did they get into trouble with their time? At the end of the exercise, allow students to finish their essays.

Which one are you going to try? Come tell me in the Facebook group!

HOW ABOUT A FREE COMMENTARY ANCHOR CHART TO HELP YOUR STUDENTS GET UNSTUCK WHEN THEY ARE WORKING ON RHETORICAL ANALYSIS DRAFTS? GRAB IT HERE.