Go buy some stock in Paper Mate because you’re about to bump that bottom line. Red Flair pens and blue Flair pens should be on your list of required classroom supplies and your list for Santa because they are going to change completely the way you teach students to analyze both fiction and non-fiction.

Why Analysis is SO HARD

The two most challenging skill sets to teach to mastery are paraphrasing and analyzing. These two processes require the brain to make connections that no other skills require. Put way too simply, analysis is explaining how a fact, excerpt, detail, or example illustrates the truth of the topic sentence and, by extension, a thesis statement.

Analysis is explaining how a fact, excerpt, detail, or example illustrates the truth of the topic sentence and, by extension, a thesis statement.

Huh?

Explain it like that, and you’ve already lost your adolescent audience. But make it visual and give them some markers, and you’re on your way to pulling from those minds the most amazing literary analysis and rhetorical analysis you’ve ever read. Here are some steps for introducing the concepts, and they apply to both fiction and informational text:

Step 1: Get on the Same Page with Terminology

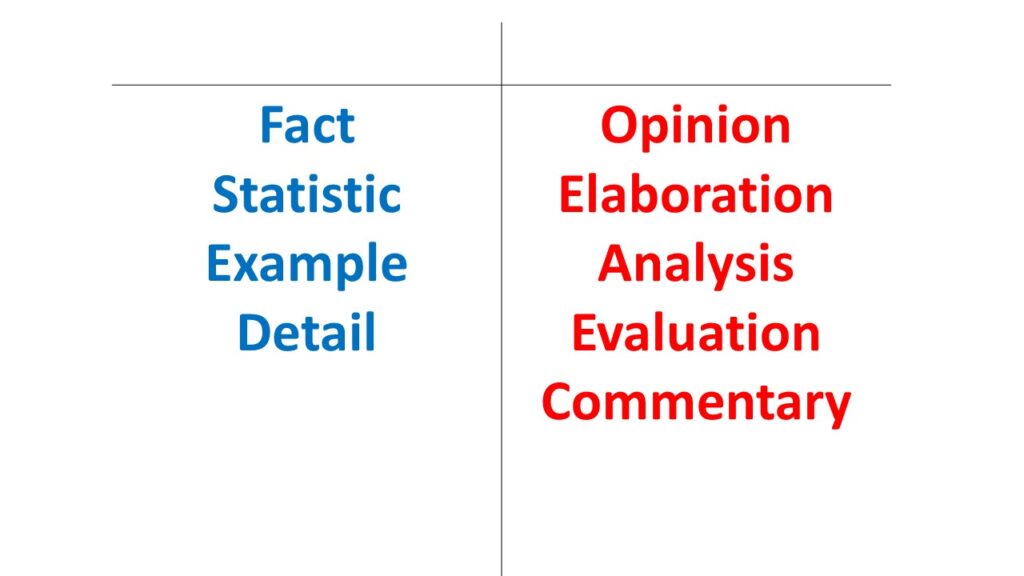

Give students this list of terms: fact, opinion, analysis, commentary, detail, statistic, example, elaboration, and evaluation. On a white board or chart paper, create a T chart and have students sort the words into just two columns and then label the columns. Students might do this in pairs first before the class talks about it as a whole group. As you work with the class to categorize, write all “fact” words in blue and all the “opinion” words in red. The final T chart might look something like this before you decide as a class what the labels will be:

From now on, every time students plan, write, back map, etc., they are doing so in blue and red. Blue is FACT and red is OPINION. What you call them is up to you, but you need to be consistent, and ideally, every teacher in your department or team uses the same terminology. When I taught at Grimsley HIgh School in Greensboro, North Carolina (Go Whirlies!), our department chair went to a Jane Schaffer workshop and came back and trained our sixteen-member team like a religious zealot. We all bought in and started using CONCRETE DETAIL and COMMENTARY. A few years later, our Department of Public Instruction came out with a writing rubric that used SUPPORT and ELABORATION, so I used those for years and years. Now I’m on CONCRETE DETAIL AND ANALYSIS.

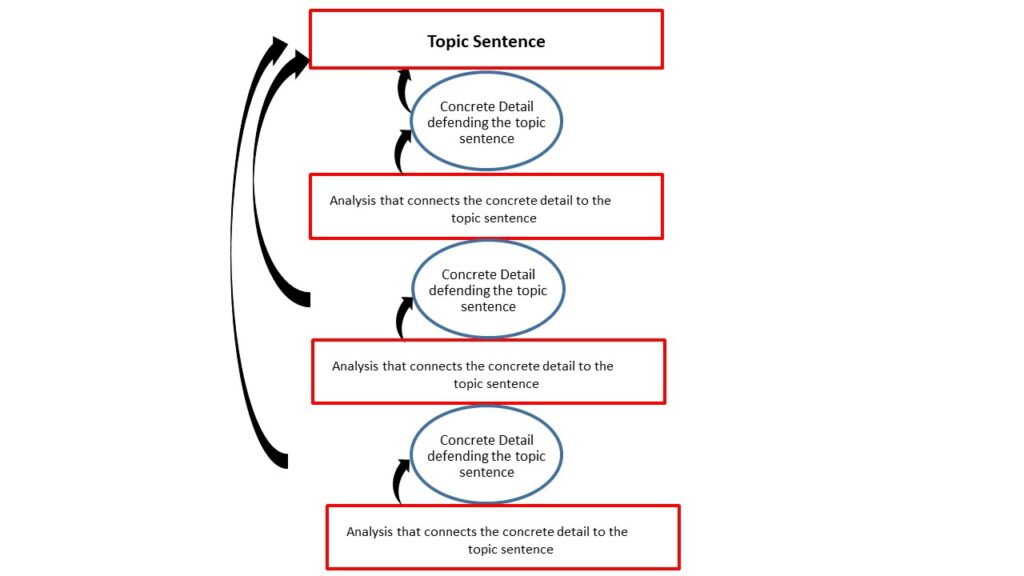

Step 2: Illustrate to students that the job of analysis is to connect each concrete detail to the truth of each topic sentence.

For training purposes, we live only at the paragraph level for a while, and we put topic sentences first. The topic sentence is always OPINION, so it is always RED. A concrete detail is always factual; it is something a student can point to in a passage, so it is always BLUE. Analysis is opinion that connects the BLUE support to the RED topic sentence. Depending on the level of student, a paragraph might have two or three blue concrete details, and each detail will have corresponding RED analysis.

Step 3: Scaffold with Meaty, Debatable Topic Sentences

The teacher is the best reader and writer in the room, so modeling is a must here. A topic sentence must be debatable; if it isn’t, the student will hit a brick wall. They need to get good at building debatable topic sentences, so I start by giving them the whole thing. We then move to a topic sentence with a hole that needs a debatable word, and then we move to completely original topic sentences. It took me a while to figure out that when a student can’t come up with a concrete detail or corresponding analysis, the problem is the topic sentence.

Step 4: Work on Creating Really Specific Concrete Details

I tell my students that a good concrete detail is like a laxative. (I know, gross. But they get it.) If a detail is specific enough, the analysis will flow. If the detail is too general, analysis is not going to happen. We do sorting exercises to help students understand the difference between concrete details, general details, and the author’s own commentary. Once students can tie a solid concrete detail to a solid topic sentence, then we start working on analysis.

Step 5: Scaffold with Guiding Questions

When I’m training students (and yes, it’s formulaic, but the brain looks for patterns, so just let it go), I give them a red topic sentence, a blue concrete detail, and then two to four questions to help them write a statement that connects the blue to the red. I create exercises in which I give students ten sentences of “analysis” and have them decide in teams which ones will work. Once they can recognize analysis and then write it within a framework, I start letting them write full, original analysis.

Step 6: Write in color.

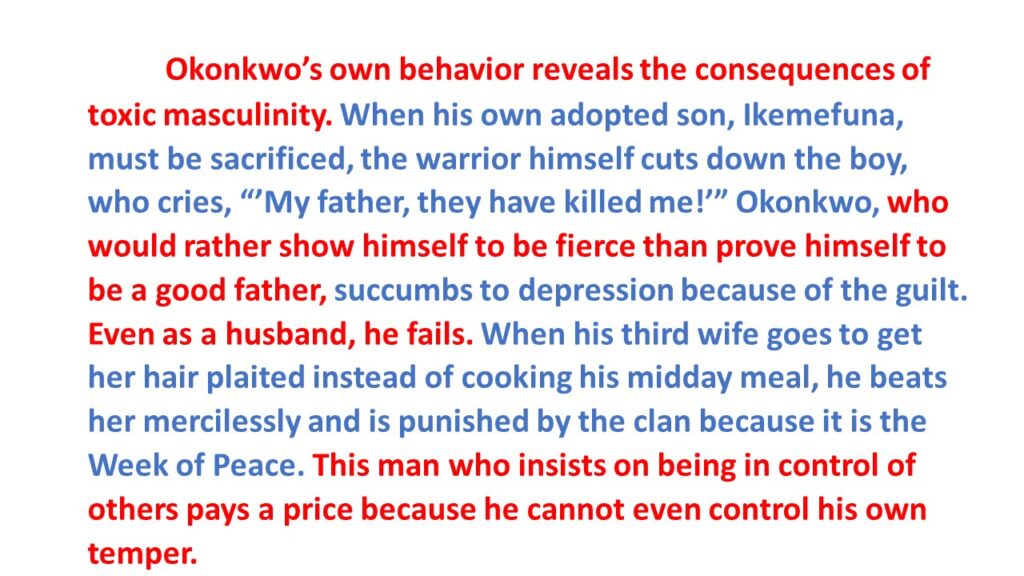

Here’s where the pens come in. Students will write each element in a graphic organizer in red and blue. Once their templates are approved, they can move on to paragraph construction. This is an example of a literary analysis paragraph for Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, but a rhetorical analysis paragraph would look similar.

Step 7: Work on sentence combining and transitions.

If you’re a Jane Schaffer fan, you call this weaving. It’s a style thing and is actually one of the easier parts of the process. Creating this flow is part art and part science, part finesse and part grammar.

Step 8: Refine.

We hangout in Steps 4 through 7 for a LONG time. Once they stop writing themselves into a corner with junk details and shallow analysis, they can get to a full essay.

Step 9: Work on Thesis Statements.

I know this seems out of order, but I want students to master sentence-level and paragraph-level analysis before they create that idea that will control an entire essay. With my freshmen and sophomores, I would always use this order, but with my AP English Language & Comp students, we might hop in and out of thesis work based on which mode we’re in.

Step 10: Tack on Introductions and Conclusions

An introduction is icing on the cake, and a conclusion is a gorgeous piece of decor on top (If it’s the right one, it’s perfect. If it’s awful, it should just be scraped off). I teach my AP Lang students to write a thesis statement, jump in, and skip the conclusion. (Scandalous!)

Step 11: Circle Back to Style with Transitions and Word Choice

This step could fit anywhere, but I dropped it here because these two issues may just be my lowest priorities. With AP Lang, I might move word choice up a bit, but transitions are the least of my worries.

Want an anchor chart to help students improve commentary? Grab that here.