What you think you know what might be so. That truth applies to AP Language rhetorical analysis as well as any other area of life.

I was today years old when i learned that turkeys can fly. (Les Nessman, you were right all along.) Just recently, I learned that the hole in a spaghetti spoon was there for measuring servings of noodles. Who knew!?

Sometimes, we just glide along, teaching the way we were taught, operating the way our co-workers operate, often under some false assumptions. We’re going to look at five of those.

MYTH #1: Students are supposed to dig into the nitty gritty on Question 2.

Twenty years ago, we taught students to analyze style. Style is part of rhetoric, but current prompts have expanded past style. Back then, We trained them to nit pick, to look for minute examples of devices and expand on the author’s use of those. In fact, I used to teach my students to devote separate paragraphs to diction, figurative language, etc. That method of organization is still perfectly valid, but it steers students away from the big picture of rhetorical development, where they are looking at the macro elements like organization and tone.

A sure sign that a student is headed down the nitty gritty path is a thesis statement that includes micro devices but misses macro strategies. For example, if a thesis lists diction, metaphor, and syntax but never mentions the author’s tone or organizational structure, the student might be missing the forest for the trees.

How do you get students to think in the MACRO versus the MICRO? Start with tone. Train students to look for tone shifts, which often are a dead giveaway for organizational shifts. If students organize their essays the way the author organized the piece (one paragraph per section or tone), that student is more likely to be in MACRO territory.

I’m teaching a webinar on this strategy in July, and I’ll announce the dates to my email list,, so if you’re not subscribed, you can do that here, and I’ll send you a super helpful anchor chart to help students get unstuck when they’re writing a rhetorical analysis essay.

MYTH #2: Students have time to annotate on the exam.

Yeah, they really don’t. Students have two hours and fifteen minutes to read and respond to three prompts. The first fifteen minutes are for reading, making notes, and deciding the order in which they will respond (on the paper-pencil exam; on the online version, they cannot choose the order).

If a student evenly divides the remaining time, that leaves 40 minutes for each essay. As opposed to spending ten or fifteen minutes pouring through every line and filling the margins with notes, I tell my students to look for tone shifts or tone layers, note where those are signaled, and organize their own essays accordingly.

To make sure they are dead on with author’s purpose, I have students sketch out a quick SOAPS or rhetorical triangle diagram, write a thesis, and go.

In-class prompt dissection is different. In the training stage, that step alone could take 40 minutes.

Process essays are different. When there is plenty of time, we want students doing it all–scouring the prompt twice, annotating, writing the thesis, outlining, drafting, writing an intro/body/conclusion draft, revising, rewriting, and proofreading. All of that is NOT going to happen on on the AP Lang exam in 40 minutes.

MYTH #3: A timed rhetorical analysis essay has to have an introduction and conclusion.

40 minutes, remember? On the exam, we’re asking a sixteen-year-old kid who is already a nervous wreck to pull off three college-level essays. You and I both know that the conclusion is going to be terrible, so I want my students to devote that time and brain power to defending that stellar thesis, not putting a tidy (and useless) bow on the poodle.

This one is a bit controversial, I know. With a process essay that students are writing with me at a slower pace, we have time for the refined skills like easing the reader in and setting up the thesis. If a student saved Question 2 for last because she wanted to bank time for it, she is not at her leisure to design Mrs. Kratzer’s funnel-shaped intro and peanut-shaped conclusion.

Now if she has the time, if she sailed through synthesis and argument and has an hour to work, then A) I’m a little bit worried but B) She can slow down her process, craft a sophisticated introduction, and perhaps even write a conclusion that actually concludes something and leave the reader thinking.

My guess is that she won’t have the time. Let’s say she’ didn’t bank the time but rather saved the worst for last and only left 30 minutes for the hardest prompt. She needs to write a fantastic thesis statement and two to three body paragraphs that defend that thesis.

If she does decide to skip the full intro and conclusion, we just all need to pray that this student’s class doesn’t get a first-time, veteran high school English teacher as a reader. Heaven help us when that five-paragraph essay bias rears its ugly head.

MYTH #4: Rhetorical analysis can be taught to mastery as an isolated unit.

Because I’m a linear thinker, I teach the AP English Language & Composition curriculum in chunks. I begin with rhetorical analysis and move into the rhetorical modes then argument then the research process then synthesis. However, because of the nature of rhetorical analysis, I have to keep spiraling back to it in various ways. Read more about how to spiral rhetorical analysis.

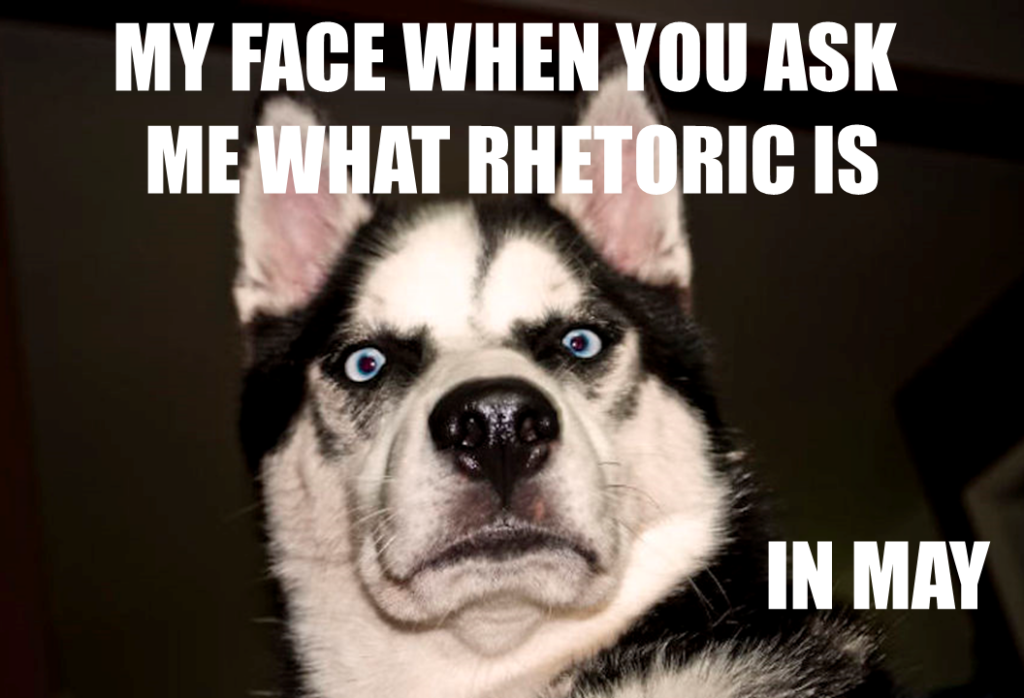

In short, if you teach rhetorical analysis first quarter and then fail to revisit it before the May exam, your students are going to look at you with that blank stare, and you’re going to look back at them with this one.

Proficiency, however, is possible on that first round. What’s the difference? Proficiency means you can do it. Mastery means you can do it well, teach others to do it, and possibly do it in your sleep. I do a deep dive into rhetorical analysis for most of first quarter and then come back to it to keep students’ skills sharp. You can read more here about the way I pace my course.

This video on planning options might be helpful as well.

MYTH #5: The best way for students to learn to write rhetorical analysis is through multiple full-length essays.

Eventually, yes–you want students knocking out a rhetorical analysis in 40 minutes or so, and you want them writing full process essays in and out of class. HOWEVER, those exercises are for refining, not training. Rely on paragraph-level writing to build their skills and save your sanity.

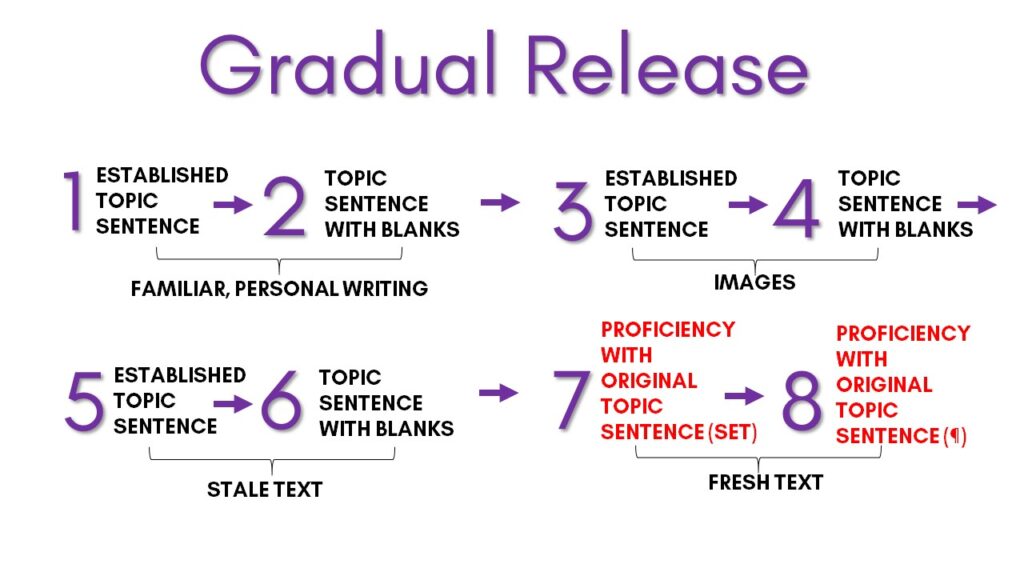

We want students defending a controlling idea in the form of a thesis, and I have found that the best way to make that happen is to train them on a micro level by having students practice with what I call sets, short topic sentence-evidence-commentary segments of analysis. We write these to mastery level then move on to paragraphs.

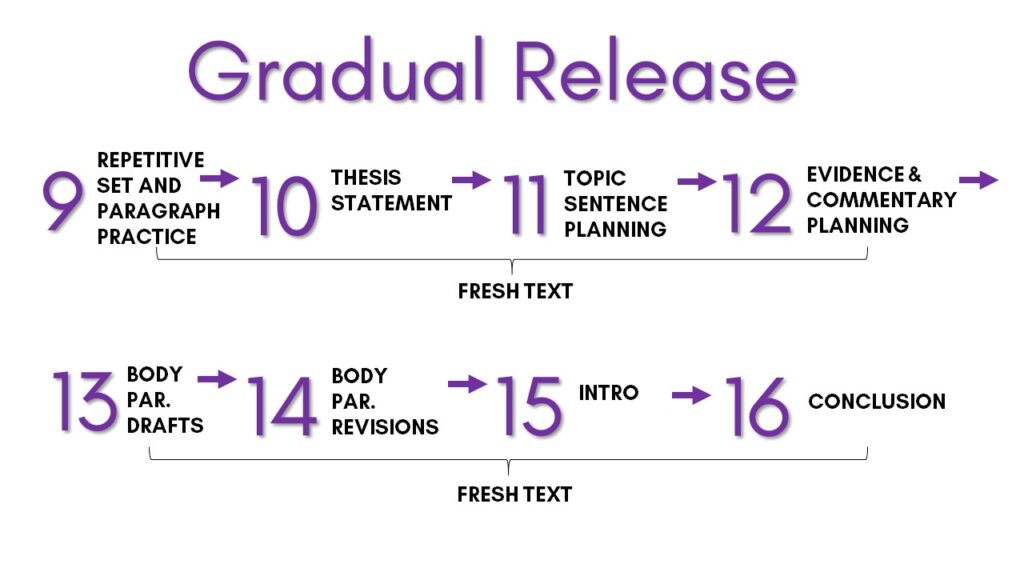

Below is a two-image snapshot of the process I use to teach rhetorical analysis to mastery. What you don’t see on here is the baseline essay I give at the beginning of the year, but you can get a good sense of the way I introduce topic sentence defense.

One of the reasons I teach writing this way is that I don’t want to drag home 100 bad, full-length essays. It’s a waste of my time and theirs. What makes more sense to me is that I get students to master on the micro level and work them up to full-length essays. By the time we start writing the introduction and conclusion, they are masters at evidence and commentary.

Sometimes, we help our students by thinking outside the box–just like we ask them to do to get that sophistication point. It’s mythology that we need to require students to do in 40 minutes what we give them days to do with a process essay. It’s also mythology that we should work ourselves into an early grave by assigning 20 full-length rhetorical analysis essays in an AP English Language class in the first 20 weeks of school. Let’s give everybody an expectation break.

Related Articles

Why Start with Rhetorical Analysis?

How to Spiral Rhetorical Analysis

4 Ways to Improve Evidence in Rhetorical Analysis