Anchor papers. Example essays. Guide papers. Exemplars. Sample essays. Whatever you call them, they are designed to make slightly more objective a subjective process—the evaluation of student writing.

Whom Sample Essays Are For

Anchor sets are designed for the paid readers who are scoring the essays; they are not designed specifically for teachers or their students. The sets are, however, invaluable as classroom tools. They can provide insight into each score point in a way the rubric cannot.

How Anchor Papers Are Chosen

A set of anchor papers can be created in a number of ways, but the methods I’ve experienced pull them from field tests or the actual responses to the prompt given under high-stakes conditions.

I’ve been on several committees that choose these anchor papers, and this is how it typically works: Ahead of time, a coordinator pulls essays that appear to fit a specific score point. A larger group of teachers then debates each choice. We have asked questions like this:

Is this response typical for this score point?

Will the use of this essay create clarity or confusion readers/scorers? (In other words, Is it an outlier?)

What are the specific elements of the essay that make it fit?

Can we articulate to readers why this essay fits?

In other circumstances, a group of teachers will do some preliminary scoring, and a coordinator or question leader will choose from that stack samples that had consensus in scores. (If the readers were all over the place on any given essay, that one won’t make the guide set.)

Advisory committees will come to blows over certain issues, and the issue that I’ve seen the most is conventions. Rubrics need to be crystal clear with guidance on usage and mechanics; if they aren’t, a sentence-diagramming stickler is going to be at the table with a teacher who believes that usage requirements are racist and classist, and the process is going to get ugly. The conventions element on a rubric can be as simple as “Usage and mechanics contribute rather than distract” or as detailed as line items about comma splices and homophones.

When I was a secondary ELA curriculum specialist, I served on the North Carolina Writing Advisory Committee for our Grade 7 assessment. There were twenty or so teachers and specialists seated in a large square with the testing company suits at one of the tables. A representative of the company would pass out a paper copy of an actual student response to the prompt. We would read it and debate the characteristics of that essay and where we thought it fit.

If we could not come to agreement, that response did not make it into the anchor set.

How Anchor Sets are Used in Scoring

Student samples are for initial training and refresh calibration. When readers are learning how to apply the rubric, they get a lot of practice with scoring. By the end of initial training, a reader can usually grade accurately and quickly (and by quickly I mean more quickly than pre-calibration).

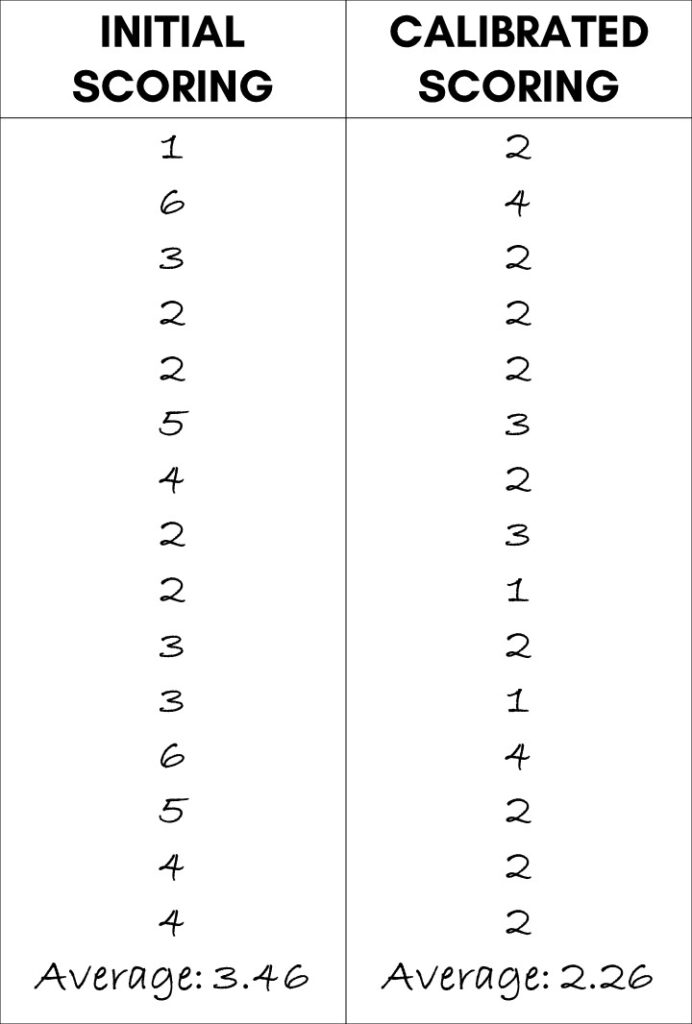

I’ve scored online for the SAT and live for the AP Language exam, and the training processes were drastically different. For the old SAT writing section, we were shown examples at each score point and then given fresh responses and asked to apply the rubric, what at the time was a fairly straightforward six-point tool. Once we were scoring accurately with consistency, then we were set free to score. If, during the scoring, a reader’s evaluations began to stray, that person would be kicked off the live reading and sent into a re-calibration process. Being “off” meant that the reader was more than one score point away from another reader on the same essay, and the scoring supervisor sided with the other reader.

In a two-reader scoring system, there is a built-in checks and balances mechanism. If I give a response a 4 and another reader gives it a 2, that response would get flagged and re-scored by someone higher up the food chain. This unfortunate circumstance happened to me once during remote a remote SAT reading because I scored just two responses and then answered a phone call without logging out. One of my two scores was off, and I was sent into a tedious calibration process that was intended to get me lined back up to the rubric.

With a one-reader system, calibration is even more important. The AP Language and Literature exam questions get one reader per response.

I’ve done one live AP Lang reading with a rhetorical analysis prompt and the old nine-point rubric. We looked at example after example after example, hashed them out together, and created for ourselves a stack of examples at each score point. During the reading, I had nine paper clipped stacks of student samples at my station. If I ever got stuck on a score, I would go back and read essays at a couple of different score points and decide where the new one best fit. We were trained back then to decide first if an essay would land on the upper section or the lower section of the rubric and then to drill down from there.

Right after being trained, I was pretty good at the initial assignment of upper or lower. I was, however, a little too generous at the top and a little too harsh at the bottom. My table leader—an incredibly patient teacher who was scoring behind me because I was new—came to me and pointed out that I was a little off and asked me to go back and read student samples at specific score points. She needed to get me lined up better with the rubric.

Here’s what I appreciated about our alignment with the rubrics at that reading: Every single time we came back from a break, we scored an essay or two as a whole group of 200 readers. This exercise served to calibrate us so that we were in agreement.

How to Calibrate Scoring

Calibration is the process of keeping a scorer or reader consistent with the requirements of the rubric.

In a former life, I was the writing curriculum specialist for a large school district, and I trained teachers in both writing instruction and scoring on the rubric used for the state assessment. This is how I calibrated my teachers, often in very large groups:

- Give each teacher a copy of the rubric and one student essay. Each teacher scores the essay without any discussion and sets that paper to the side. I do not give the score.

- I have every single teacher give me a score, and I write them all down on chart paper and set that chart to the side. We get a laugh out of how far apart the scores are.

Why are they so far apart? Teachers are coming to the rubric from different writing backgrounds, different expectations for their students, etc. They are often applying their own standards, not those of the rubric.

- We spend time looking at the tool itself, making sure we’re all clear about the language being used and the skills required by students. (One of the terminology issues that almost drove me to drink was the wide variety of ways teachers referred to commentary. Not only were teachers using analysis, evaluation, explanation, extension, and elaboration at the reading, they weren’t even using the same terminology at their grade levels or schools. I do a whole lesson on language consistency in my course The Confident Student Writer.)

- We spend hours looking at student samples, debating their characteristics at tables, deciding on scores in small groups, and then checking in with the large group. By the end of that training piece, teachers at each table are usually within a point of one another and are accurately applying the rubric.

- Now I pull out that original chart paper and have the teachers look at the first essay with fresh (but trained) eyes. We then repeat the original exercise and put all the scores on the paper for all to see. This moment is my favorite piece of the whole workshop. A whole room full of teachers goes from scattered to aligned, and it’s so fun to watch their reactions as they hear the same number called out over and over and over.

- I then talk briefly about being comfortable with any score that is one above or one below, announce the score, and enjoy the cheering.

Fighting the Standardized Rubric

I came up as a classroom teacher during the introduction to writing rubrics. For years and years and years, I would read an essay and say aloud something like, “Eh, feels like a B.” I wasn’t the only one; that’s how we all graded essays in the early nineties. An essay that would earn a B from me might earn a D from another teacher. What a mess. (It makes you look sideways at the awarding of valedictorian honors when students are being judged by different standards, doesn’t it?)

We learned how to use and create matrix rubrics, straight point rubrics, and no-point rubrics on which we only marked the skills we were looking for in that particular assignment. Even then we were doing crazy things like not showing the students the rubric until they had completed the work, as if the veiled mystery of grading would be revealed and ruined if we told students ahead of time exactly what we wanted.

So now we know better. Students get the rubric ahead of the production of the piece so that they know what skills the teacher wants to see. Now we’re getting to a pedagogically appropriate use of the tool.

How Standardized Prompt Rubrics Are Created

So how do rubrics work with a standardized test like the ACT or one of the AP English exams? A group of people get together and, using the language of the curriculum being taught, develop criteria to help readers recognize what those skills would look like if being executed.

For example, what exactly does it mean to show evidence? A rubric can reward a student whose evidence is both relevant and of high quality. There also has to be enough of it! A rubric might reward these elements separately, and a group of people—typically people well versed in (and with experience teaching) said curriculum—set the rubric. So we start with a small group of hand-selected people who decided how to reward the demonstration of a set of skills and processes.

Then it’s over. Once a rubric has been codified, evaluated, run through focus groups, strained through a field test, and baptized, it is not to be questioned, at least not at a reading.

SO DON’T FIGHT THE RUBRIC.

When training teachers to score on a rubric, I often hear evaluation of the instrument itself. It runs something like

It puts too much focus on conventions.

This flies in the face of current research.

Do they really expect students to be this sophisticated in their thinking? I know mine aren’t.

By the time a rubric for a standardized writing assessment makes its way to a classroom teacher, it is what it is. It is the standard. When we fight the tool, we just slow ourselves down or mis-score because we know better than the people who created the rubric.

Don’t do it. Waste of time.

Do you teach rhetorical analysis? Could you use a little help with commentary? Grab this anchor chart.

Using Guide Papers in the Classroom

There are so many fun ways to use guide papers with students. Here are some highly effective strategies you could implement tomorrow:

- After students have responded to a prompt, do a full-fledged calibration exercise with the whole class as described above. The activity works quite well virtually if that’s your situation, and you can simply open up Jamboard and write the scores there.

- Later in the year, host a light-hearted Calibration Competition after each timed practice. Put students in pairs, give each team a set of five responses at different score points, and read each essay one at a time. Each team writes down a score and two to three sentences defending that score. They must use language from the rubric! Have each team give a score and write them on the board. Announce the correct score, discuss using any notes provided by the Chief Reader or Question Leader for that question, and award one point to any team within one score point of that number. At the end, the award is something little like a few points on a low-stakes assignment, a homework pass, or some small office supply novelty like a three-prong highlighter. (My students would kill for these!)

- Use the student samples as models for specific skills; for example, students identify the thesis from a strong response and discuss what makes it work.

- Have students back map a response. If you give students a graphic organizer to help with planning, have them fill in that organizer in reverse with a response from the sample set. You might do this to show a balance of evidence and commentary or highlight gaps.

- Get students to compose a letter to the writer explaining what that person would need to do in order to move up one or two score points.

- If using a three-row rubric like that now used for the AP English exams, have students use three different colors to highlight what made a specific response earn a specific score on each row. (I have created student-friendly versions of the AP Lang free response rubrics. You can get those for free here.)

Want to stretch your brain (and your patience with fellow humans)? I need to create an anchor set for a synthesis prompt. Want your students to do the writing? I’ll send you the prompt for free. Just email me at [email protected]. You can read more about my approach to the AP Language Question 1 prompt here:

AP Language Synthesis Review Tips

How to Guide Students Toward Better Image Analysis